An Open Letter to

All Mennonite Newsgroups

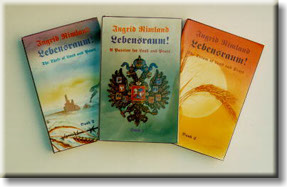

In his review of my trilogy, Lebensraum! depicting the Mennonite experience for the past 200 years, spanning seven generation and several continents, history professor John Juhnke of Bethel College in Newton, Kansas stated in a recent Mennonite Weekly Review:

"On my desk is Lebensraum! by Ingrid Rimland . . one of the most audacious novels in all of Mennonite literature."

What followed that opening salvo was a steely, stellar book review that tells me, among other things, that Dr. Juhnke is politically correct. He hints that I have compromised my heritage as a Russian-born, German-descent Mennonite - not because I wrote another book that might upset some Mennonites, but because I am an Internet Revisionist aligned with a decided "villain" - a controversial German-Canadian human rights activist, publisher and TV producer, Ernst Zündel, who is defending certain concepts and beliefs most Mennonites would definitely not approve.

One of them is, divines the good professor, that I, like Mr. Zündel, am challenging the "Jewish Holocaust" for my own wicked ends by juxtaposing it to ethnic horrors of my own, drawn from my personal experience in World War II as a small child. I am, therefore, still harboring feelings for Hitler!

Having divined the "obvious", Professor Juhnke then concludes:

"One revisionist acclaims Rimland's Lebensraum! saga for endowing the revisionist movement with needed cultural and literary substance. Mennonites might wish that their own history had not been appropriated for a purpose so allied with racist hatred."

To make that giant mental leap is definitely politically correct!

That is exactly what Canadian Customs likewise concluded when it seized some $15,000 (Can) worth of Lebensraum! as being far too hazardous for grown-up Canadians to read. While doing so, and for good measure, they also confiscated "Furies" - the book I wrote about my handicapped child - a title which, in 15 years, has yet to elicit one single negative review!

(So far, they haven't yet snatched "The Wanderers", the award-winning novel I call my "baby epic" and the precursor to my trilogy, Lebensraum! No doubt that is bound to happen next in censor-happy Canada!)

In my affidavit submitted to Canada Customs in a legal challenge following that confiscation of my intellectual property, I wrote:

In my early ethnic novel, The Wanderers , I depicted the German Army of World War II in an unconventional, "politically incorrect" way - as liberators, not destroyers. Never ever did I experience any political repercussions for that novel! By contrast, thanks to an ever more censorious political atmosphere in Canada, as transparently reflected in the detention of my Lebensraum! novels, which carry many of the themes I first broached in The Wanderers, certain historical fiction all of a sudden seems to upset certain lobbies. (...)

The German Mennonite wheat-growing community depicted in these novels - for centuries reflecting an uncompromising ethnic cohesion and a fundamentalist and pacifist approach to life and war - was founded in the Ukraine in 1789, and was substantially eradicated in the Communist ethnic cleansing purges of the 1930s and early 1940s. In my trilogy, I bring to life the tumultuous events and the vast changes which occurred in that era, as well as the attitudes of the Mennonites' "American cousins" who had left the Ukraine in 1874 and settled in the plains of Kansas, again as wheat farmers specializing in the hard winter wheat they brought as immigrants from Russia.

Civil wars, depressions, famine, anarchy, conflicts between religion and atheism, between capitalists and communists, between traditionalists and liberals, between nations and between peoples led to enormously bloody strife in Europe - an era hardly ever covered fairly and objectively in the Western world, simply because most ethnic-German intellectuals, at least in Russia and largely in Germany, did not survive those times. My own father, a high school principal in the Ukraine, was exiled to Siberia in 1941 - for no other reason than that he spoke German and was part of a savagely persecuted religious minority. I never saw my father again. Many members of my family and ethnic group perished for the same reasons in genocidal purges.

I have spent 17 years researching, writing, and eventually assisting in the publication of these novels that depict the suffering inflicted on a small ethnic minority due to political and religious persecution, making sure that my characters correctly reflected the spirit, attitudes and feelings of the times. As a first generation eye witness immigrant who lived in Mennonite communities on three continents and who witnessed German ethnic genocide first hand, I have a duty to write about what I saw, honestly and truthfully, and to use my talent to give voices to those Germans and German-descent peoples who were tortured, exiled and killed in large-scale, Soviet-style ethnic cleansing - brutalities of which the Western world knows very little.

In writing these three detained, "politically incorrect" books, I did not intend to promote hatred against any identifiable group. I tried to eliminate hatred against Germans who have been falsely broad-brushed in unfair and simplistic ways by Hollywood and self-serving political activists with a transparent, vested interest in one-sided, simplistic stereotyping of Germans. In fact, I went out of my way to describe good Germans and bad Germans, good Russians and bad Russians, good Jews and bad Jews. I expressed a literary opinion based on my upbringing as a surviving member of a savagely persecuted and decimated German-descent Mennonite minority, my ancestors, and on the effects of religious and cultural values clashing with craven politics not of my ancestors' making and often far beyond their understanding.

Any complex, intelligent novel will depict complex characters. The basic historical truth of my novels is that this small German-descent Mennonite community - uncompromisingly ethnically cohesive, inoffensive, apolitical and pacifist - was caught up and destroyed by the Communist regime intent on ruthless eradication of cultural differences and ethnic values that were not state-approved and, hence, deemed "politically incorrect" and thus criminalized. This is one of the most important themes which runs throughout my three detained novels - the brutal social intolerance and legal and judicial punishment inflicted by politically empowered censors on victims holding "politically incorrect" views.

Ernst Zundel is on trial in Canada for politically incorrect views, some of them posted on the Zundelsite, a website I maintain in California. The body judging him, misnomered "Human Rights Tribunal", has in a recent ruling declared that ". . . truth is no defense!"

Does that not make you think? Is that still "democratic" Canada?

In one of my novels, a Mennonite farmer pleads with his tormentor, a Soviet Kommissar: "But I am innocent! You cannot prove my guilt!"

To which the Kommissar replies:

"But you don't understand! You have that wrong and backwards! I do not ***have*** to prove your guilt to you. ***You*** have to prove your innocence to ***me.***"

That's what is happening in Canada. That's why my trilogy is banned.

I say that in a civilized nation, historical truth must be a defense. I say that a country that makes the telling the truth an offense is no longer a sovereign country.

A novel is a stylistically artistic rendition of true-to-life experiences where motives propelling its characters run deep. My individual characters in my ethnic novels experience a complex range of emotions - some of them entirely appropriate and legitimate, given the circumstances of the times in which they lived and died - but now in our "politically correct" times harshly persecuted even in Western democracies in systematic psychological warfare tactics and media-fed vilification campaigns.

Shout "Racist!" - and people turn pale. Shriek "Nazi!" -and people will scurry. Has it not made us cowards - whether the labels were valid or not?

I tried to create characters who come across as living, struggling, bleeding human beings - not one-dimensional, grotesque, simplistic cardboard automatons straight out of Hollywood.

Professor Juhnke, teaching Mennonite history in a Mennonite college, has this to say in his review:

"The Germans, Rimland says, suffered a worse and less deserved Holocaust than the Jews did . . . Even if her historical argument were accurate, no amount of vivid storytelling could make up for such spiteful didacticism."

Those are strong words. I would like to reply if I may:

My people's broken bones lie in Siberia. It shocks me that I heard him say these words.

I am a novelist and artist. I sit at my computer and try to paint pictures with words. An artist seeks to present a refined and distilled essence of something that moves heart and soul. A novelist does more - he or she tries to distill the essence of moral conflicts that wrench and tear and often even kill heart and soul unless they are resolved with deeper understanding.

Each word and each sentence follow careful reflection and thought. I have spent almost sixty years in thinking and reflecting about what happened to my people, the Russian-German Mennonites, in several world wars. Why did my cousins in America, actively or passively, fight Hitler by choosing as their ally the bloodiest murderer in human history, the monster Joseph Stalin, who almost succeeded in murdering me and all of my kin in devastating ethnic cleansings?

One of the many moral conflicts in my trilogy is that the Mennonite community in my fictitiously created town called "Mennotown" in Kansas was losing its essence and cohesion because it blithely allowed the undermining of its ethnic glue that held its forebears' towns and settlements together and let them prosper in the Lord for practically half a millennium on several continents.

Another moral conflict I have painted in my novels is that this hitherto rural and largely agricultural community did not, and does not to this day, allow the expression of loyal dissident thought - in my opinion, to its own detriment.

A third moral conflict I painted in Lebensraum! is that there is still a part to Mennonites' own history they would as soon not know. It makes them very squeamish to think that there were Russian-German Mennonites who did, indeed, greet Hitler as a savior - and quite legitimately so. Who wouldn't have, against their backdrop of bloody ethnic cleansings in the grip of the Stalinist henchmen that purged them of most of their men? Those who were safely tucked away in the wheat fields of Kansas did not know what was happening in Russia. Their sense of history, says one of my main characters, "Erika", was like an unkempt garden where weeds grew that do not belong. These people didn't - and still don't, as Dr. Juhnke book review makes very clear, for he is one of them - have the requisite facts and full picture to comprehend themselves in their dislike about their cousins' "Nazi past".

A fourth moral conflict I described in my three novels is the portrayal of a sectarian religion once so deeply rooted in an apartheid ethnicity that it was unassailable and practically indestructible even under brutal and repressive dictatorial regimes the likes of which few people can imagine. Why is it going belly-up in our seductively prosperous times where preachers are canvassing Third Worlds to find new converts because they are losing their children? In olden days, the Church was like a rock!

These are vast themes requiring rigorous, unblinkered thinking expressed by subtle nuances of words. One does not write that kind of a novel by changing nothing but the names. A novelist who knows what he or she is doing will craft a novel's characters from life's experiences but fit them into fiction because a novel is a literary vehicle permitting condensation. Vast, complicated themes treated with skill and sensitivity in a fictitious setting evoke emotions that help the storyline along. The reader, swept up in a current of feelings, thus makes himself part of the story by drawing on his memories - or finding echoes in his own identity! That is what Lebensraum! is really all about.

The Mennonite child, Mimi, who tells the Kansas preacher, Dewey, who comes to starving Russia in 1922 to bring American relief: ". . . these alms are not from love" knows that her destitute people, immersed in a desperate, politically incorrect faith forbidden at the point of gun in Soviet Russia, could well be shot by Communists for owning a family Bible. From her own frame of reference, the hungry child believes that she is fully justified in telling a small lie to Dewey, believing him to be a spy. But Dewey, dangling food in front of her, sees only a child in need of some moral "correcting" and wants her to apologize and say a prayer first - as it is done in Kansas. She knows she cannot do that. It is too dangerous. Self-righteously, he withholds food and sends the starving child to bed for punishment. His cruelty, born out of ignorance, wounds an impressionable child so deeply that after a gruesome youth in the grip of the Red Terror, this traumatized youngster becomes an ardent Führer follower. The Führer gave her faith and food - and Dewey withheld one, short-circuiting the other.

Thus grew out of a small but nonetheless important incident intense dislike between the preacher and the child and made them enemies for life. Thus are societal conflicts born - with roots deep in misunderstandings and incomplete knowledge of facts.

Professor Juhnke thinks my literary treatment of the tragedy of the respected community leader, Jan Neufeld- a man so driven to despair by domino-effects in the Depression years that in the end he snaps and causes murder and then suicide - is wickedly deceptive. Professor Juhnke writes disparagingly that ". . . Rimland invents a disaster for Mennotown" which he deems false because Kansas Mennonites, he says, were thriving during the Depression.

I have interviewed many Mennonite farmers in years of research for my books who would vehemently disagree with what Professor Juhnke understands was "Kansas history" when Franklin Roosevelt came to power - but that is not the point. The point is that this literary "liberty" describes the tragedy of one good man who sees himself forsaken in a society gone mad with liberalism expressed in the New Deal that hands some undeserving, unwashed transients willy-nilly all his land, his savings and the safety of his old age - for which he slaved and prayed. It is humiliation overload - too much for one good man. America turned left when Roosevelt came to power - and never again was America the same. Ask any Kansas farmer.

Professor Juhnke thinks that I, as a Revisionist, believe ". . . the Jewish Holocaust is of minor moral significance compared to the Holocaust which Joseph Stalin and his allies wreaked upon the blond, blue-eyed Aryans." He scolds that ". . . this is not grand tragedy but petty comparative victimhood."

To that I say that I feel shame to know that a professor of Mennonite history would say a thing like that.

Some people may prefer the artificial spin-doctored version out of Hollywood to knowing what really happened to their kin in Soviet Russia. But anyone who has survived the Soviet Holocaust, the way my Russian-German people did, would take objection to his statement that telling of that blood bath tragedy is ". . . petty comparative victimhood."

Another point - the literary voice of "Erika", the novel's narrator.

I am not "Erika". I was a mere eight years of age when Germany was bombed into the stone age by the Allies in 1945 and the Red Terror overran that country. My own experiences did not match "Erika's" on every single point. What "Erika" experienced in the last days of World War II was told to me in Argentina in 1953 - not by a girl but by a 22-year-old man who tearfully recalled how he was put behind an anti-aircraft gun at age 14 atop a dying city.

And, finally, to what Professor Junke thinks is my "ideological agenda": Maybe he can divine as well what is inside my head and heart, but I can safely say that I have no intention of resurrecting the Third Reich right on the Internet. I am fighting for freedom of speech and for unimpeded access to what ***was*** our history - not what self-serving lobbies would like to force-feed us.

We Germans have a right to our own history and to defend ourselves against false accusations. What I am doing in my work as a Revisionist is not from "racist hatred." It springs from love for what once was and is now almost gone - a time where it was safe and good and right to have blue eyes, blond hair and pride in one's own roots. It's barely safe today. It won't be safe tomorrow unless we look at all of history and try to understand.

Ingrid Rimland, Ed.D.

.jpg)